Gdańsk and Cleveland: Twin Cities and Twin Lighthouses

– Written by Ezra Ellenbogen

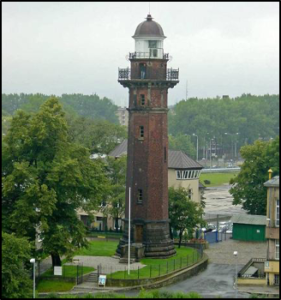

The Gdańsk Nowy Port Light, inspired by the Cleveland Harbor Lighthouse

Photo Credit to Nancy J. Rau via Lighthouse Digest

In 1893, a delegation from Gdańsk, Poland, visited Cleveland on their way to the World Exposition in Chicago.[1]There, the group saw the 1873 Cleveland Harbor Lighthouse, known as one of the most impressive American lighthouses in history. Later that year, the lighthouse had a Polish twin. Gdańsk’s Nowy Port lighthouse went into operation the following year, and even played a part in World War Two.[2] Gdańsk and Cleveland have had a long history of immigration, cultural exchange, and lighthouses, among other things.

Gdańsk (pronounced g-Dy-an-sk) and Cleveland originally pursued a sister city relationship under Mayor Ralph J. Perk, and the partnership was established in 1990 under Mayor Michael R. White.[3]

Polish immigration to Cleveland was critical to the city’s history, especially during its industrialization. Poles constitute one of the largest ethnicities in Cleveland and nearby areas.[4] The first major settlement of Poles in the Greater Cleveland region occurred in the late 1860s, in Berea, a suburb located south of the Cleveland Hopkins International Airport.[5] By 1870, 77 Poles lived in Greater Cleveland. Polish immigration to Cleveland soon picked up – cultural and political pressure and oppression in Prussian and Russian Poland drove a lot of Poles away. At the same time, Cleveland industries were rapidly growing, and transportation across the ocean was inexpensive. By 1920, Poles in the city numbered 35,024, with the highest amount of growth seen between 1900 and 1914. The entire state of Ohio reflected similar patterns, with the Polish population soaring to 67,579 by 1920.[6]

From the 1870s on, significant Polish neighborhoods began to form. Major early concentrations of Polish immigrants included Rolling Mills in Newburgh and the E-65th-Fleet Avenue area. The latter of the two saw significant growth from the 1920s to 1990s, and is now known as Slavic Village or Warszawa. The second major Polish settlement was Poznan, around 79th Street and Superior Avenue. The third early major Polish settlement rose about in Tremont, called Kantowo. In 1882, the Cleveland Rolling Mills Strike led to a considerable growth in Cleveland’s Polish population. Primarily Polish immigrants were recruited in New York to break the strike. Poles became the most prominent group in heavy labor and industry in the city.

Religion was a very important force in early Polish Cleveland politics. In fact, it was the center of the community’s largest conflict. Local church politics drove a division in the city after the removal of Father Anton F. Kolaszewski from the St. Stanislaus Parish in 1892. These church politics heavily divided the community, leading to the establishment of separate newspapers and fraternal organizations, and it even became a force that influenced local elections.

The Polish population of Cleveland peaked in 1930 with 36,668 people. By then, the Polish community of the city had multiple newspapers, banks, churches, and more. Even though religious conflicts within the community had worn down, political differences became chief divisions of Polish communities. Poles in Kantowo, which was originally settled by mostly Russian Poles, tended to be Socialist and tended to support Marshal Joseph Pilsudski. Poles in Warszawa, which was originally settled by mostly Prussian Poles, tended to be in favor of Ignace Paderewski. This was incredibly divisive for Poles in Cleveland. Even the two newspapers reflected the split, with The Wiadomosci being pro-Pilsudski, whereas The Monitor was anti-Pilsudski. Unifying Cleveland’s Polish community, even with the help of organizations, was difficult.

The German invasion of Poland temporarily put the issue aside. However, after World War Two, political divisions became prominent again, this time over opinions on the new Communist state of Poland.

Cleveland’s Polish community was much less divided on American politics, especially after the Great Depression. The city’s Polish community has been predominantly Democratic since then. One important thing to note is that Warszawa and its people have been represented much more within Cleveland politics than other Polish communities. Prominent Polish political figures from Cleveland include Joseph Sawicki, who was elected to the state house in 1906 and to the municipal court in the 1920s and 1930s.

After the 1930s, Cleveland’s Polish population began to decrease. It rose and fell numerous times for decades. However, nowadays, the urban area of Cleveland’s Polish population accounts for almost 33% of the entire state of Ohio’s Polish population.[7]

Cleveland and Gdańsk saw decades of positive interactions, trade, and events before tragedy struck (warning: mention of murder). On Sunday, January 13th, 2019, Paweł Adamowicz, a six-term mayor of Gdańsk, was stabbed brutally at a charity event in Cleveland; he died the next day at the age of 53. Adamowicz was a well-known liberal mayor who made historical strides in defending the rights of immigrants, refugees, and LGBTQ+ people in Gdańsk. The assailant had been released from jail within the past month, and blamed Adamowicz’s former political party, Civic Platform, for his jailing in 2014 following violent attacks.[8] A national mourning was held from the 18th to the 19th of January across Poland. Numerous cities, including Gdańsk and Warsaw, held events of mourning.

Cleveland and Gdańsk’s partnership have had a positive legacy of immigration, cultural exchange, and more, even if there is a tragic event that taints it. Adamowicz will live on in Cleveland and Gdańsk’s heart. As sister cities, the two have built each other up, and it is important to recognize all that has come from their partnership, as well as to keep Adamowicz’s legacy alive alongside it.

– Ezra Ellenbogen

Ezra’s blog: One Page Stories

[1] https://www.lighthousefriends.com/light.asp?ID=282

[2] http://latarnia-morska.pl/en/lighthouse-gdansk-nowy-port/

[3] https://case.edu/ech/articles/cleveland-sister-city-partnerships

[4] https://www.cleveland.com/datacentral/2011/10/searchable_database_shows_ethnic_breakdown_for_ohio_cities.html

[5] https://case.edu/ech/articles/p/poles

[6] http://ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Polish_Ohioans

[7] https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=SELECTED%20SOCIAL%20CHARACTERISTICS%20IN%20THE%20UNITED%20STATES&g=0400000US39_400C100US17668&tid=ACSDP1Y2019.DP02&hidePreview=true

[8] https://www.clevescene.com/scene-and-heard/archives/2019/01/14/mayor-of-clevelands-polish-sister-city-assassinated-at-charity-event