Global Heritage Trail

The Global Heritage Trail highlights cultural landmarks and immigrant heritage sites across Northeast Ohio, celebrating the people and places that shaped our region’s global story.

Explore the Trail

Navigate Between the Menus Below to Explore the Trail

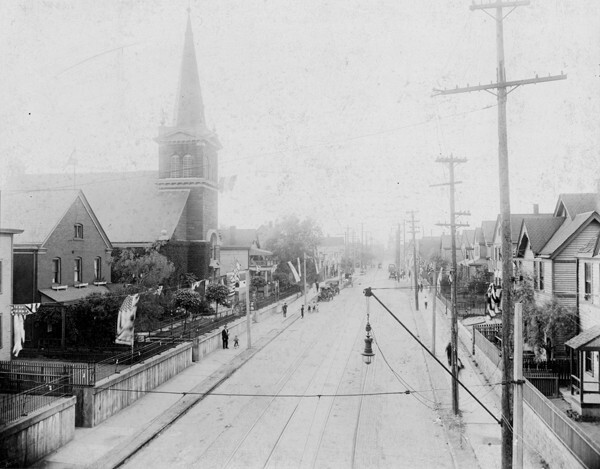

Slavic Village

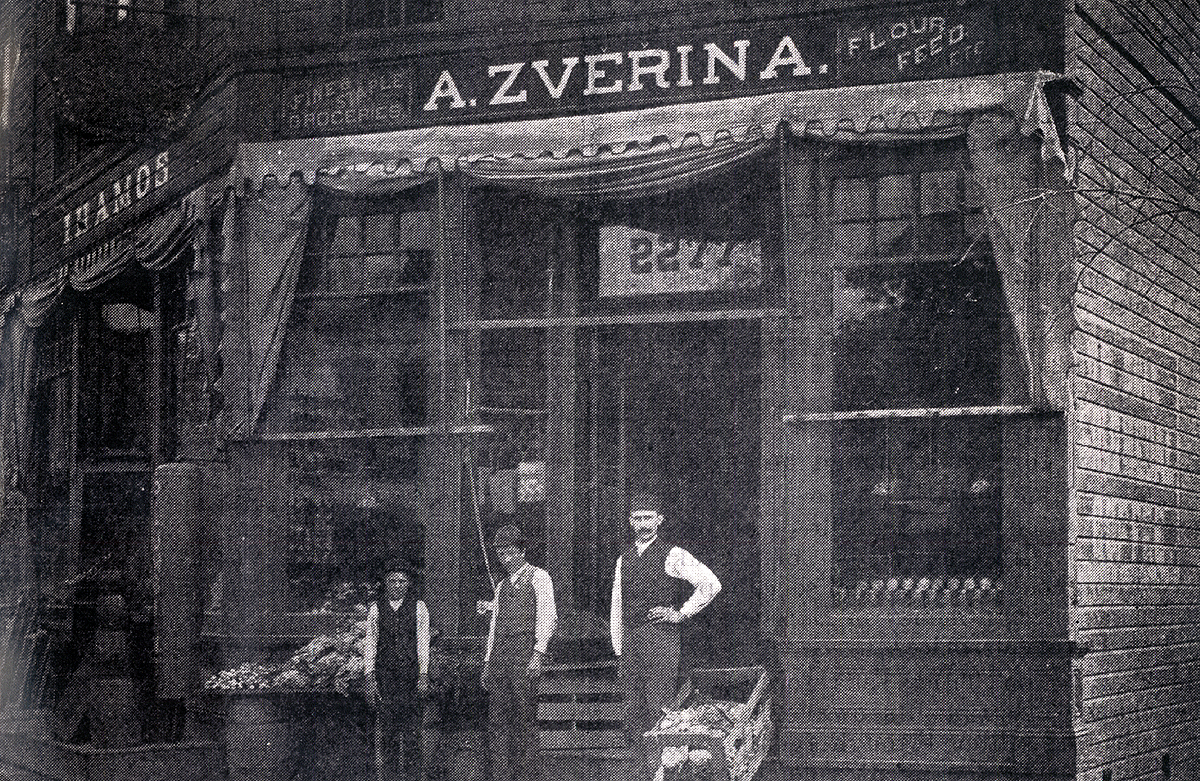

Originally known as Warszawa—or “Little Warsaw”—Slavic Village emerged with a booming Polish population and soon became one of the largest Polish communities in the United States. The neighboring area of Karlin, meanwhile, attracted many Czech immigrants. Between 1900 and 1930, both neighborhoods experienced rapid industrial growth. However, following World War II, they faced a steep decline due to suburbanization and deindustrialization. Factory closures and job losses prompted many residents to relocate to the suburbs or Sunbelt states. In response to this downturn, Polish-American attorney Ted Sliwinski led a 1977 revitalization campaign that transformed several blocks of Fleet Avenue using the vibrant Polish Highlander style, known for its rich folk art, architecture, and traditional clothing.

Slavic Village has long been home to Polish and Czech immigrants who made lasting contributions to Cleveland’s prosperity. These communities played vital roles in the city’s manufacturing and trade sectors and established thriving businesses in retail, real estate, and finance. Their impact extended beyond economics. Organizations such as Slavic Village Development (SVD) have championed quality-of-life initiatives—from workplace wellness programs to pedestrian safety campaigns, including their role as a founding member of Cleveland’s Safe Routes to School Coalition. Today, Slavic Village remains a living testament to Cleveland’s rich Slavic heritage. Visit to experience the culture, resilience, and legacy of this proud community.

Little Italy

Established at the end of the 19th century by immigrants mainly from Italy’s Abruzzi region, Little Italy remains a cornerstone for Italian life in Cleveland. One of the founding figures of Cleveland’s Little Italy was Giuseppe Carabelli, an Italian artist who came to establish a sculpting and stone masonry business. His early employees developed reputations as expert stonemasons because of their essential contributions to monumental works at Lake View Cemetery, effectively demonstrating their skills and important contributions to the community. Neighborhood life centered around Holy Rosary Church and the Alta House settlement, which together served as religious and social anchors for the community.

Italians helped fuel Cleveland’s expansion by providing critical labor for bridges, sewers, streetcar tracks, and other infrastructure. Many also worked in factories and on the railroads, further strengthening the city’s industrial base. Moreover, Little Italy offered opportunities for Italian artisans to craft monuments, tend estates, and provide tailoring services. Little Italy is also home to some of Cleveland’s most beloved restaurants, including Corbo’s Bakery and La Pizzeria. In all, the vibrant community of Little Italy is a testament to the Italian cultural influence on Cleveland. It has been an important hub for Italians to live and share their talents with the city.

AsiaTown

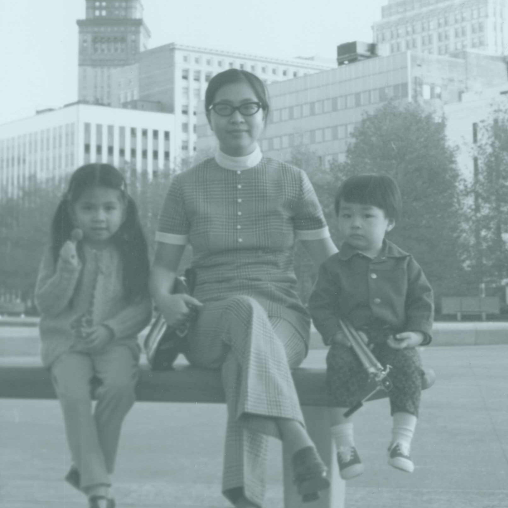

Beginning in the 1920s, Cleveland’s Chinese population was primarily concentrated along Rockwell Avenue and East 22nd Street, near the outer western edge of what is now AsiaTown. However, as the population grew during the 20th century, the area became known as Chinatown. Later in the 20th century, instability abroad and economic opportunities sparked an influx of new immigrants to this area, including Korean and Vietnamese newcomers. Today, the Korean population and businesses of Asiatown are numerous, and they are heavily involved in the Korean American Association of Greater Cleveland (KAAGC). Likewise, the Vietnamese community currently has numerous restaurants and businesses in the neighborhood. By 2000, the growing number of Korean and Vietnamese newcomers, alongside the established Chinese communities, prompted local businesses to rename the neighborhood ‘AsiaTown,’ replacing the former designation of ‘Chinatown.’

In addition to being a home for Cleveland’s Asian-American community, AsiaTown makes a significant contribution to Cleveland’s cultural, economic, and community fabric. While rooted in Cleveland’s Asian-American heritage, AsiaTown also engages in community-building efforts, ultimately working to make the neighborhood more welcoming. Several advocacy groups in AsiaTown work on overcoming issues affecting the Asian American community. Finally, AsiaTown is home to numerous Asian-owned businesses, including restaurants, grocery stores, and shops, which contribute to the local economy and provide employment, playing a vital role in the city’s growth. Be sure to stop by AsiaTown for a taste of Asian culture that thrives in our community!

Little Arabia

Often referred to as “Little Arabia,” the stretch along West 117th Street near Lorain Avenue has become a thriving hub for Cleveland’s Arab American community. This area has seen a steady influx of immigrants and refugees from countries such as Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Palestine, Yemen, and Egypt, many of whom arrived seeking safety, opportunity, and community. Over the years, Arab-owned restaurants, bakeries, grocery stores, and hookah lounges have transformed the neighborhood into a vibrant corridor of Middle Eastern culture. Shops like Almadina Market and eateries such as Jasmine’s Bakery offer everything from fresh pita to shawarma and baklava, serving both longtime residents and curious newcomers. Beyond food and business, the community has established mosques, cultural centers, and nonprofit organizations that provide language support, job assistance, and civic engagement opportunities. Little Arabia stands today as a testament to the resilience and cultural richness of Cleveland’s Arab American population.

Sources:

Cleveland Magazine, “A Taste of the Middle East in Cleveland’s Little Arabia.”

https://clevelandmagazine.com/food-drink

FreshWater Cleveland, “Little Arabia: The Rise of a Neighborhood Hub.”

https://www.freshwatercleveland.com

Ukrainian Village

Located along State Road in Parma, Ukrainian Village is a vibrant cultural district centered around Ukrainian immigrants and their descendants. Anchored by St. Josaphat Ukrainian Catholic Cathedral and a variety of Eastern European grocery stores, bakeries, and cultural organizations, the neighborhood honors the legacy of Ukrainian migration to Northeast Ohio—especially post-World War II and after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. In recent years, the area has played an essential role in resettling and supporting Ukrainian newcomers displaced by the ongoing war.

Tremont

Tremont is one of Cleveland’s oldest neighborhoods and showcases a rich tapestry of immigrant influence. German, Irish, Polish, Rusyn, and Arab Christian settlers founded churches that still anchor the community today. Walking its streets reveals a landscape shaped by faith, culture, and resilience.

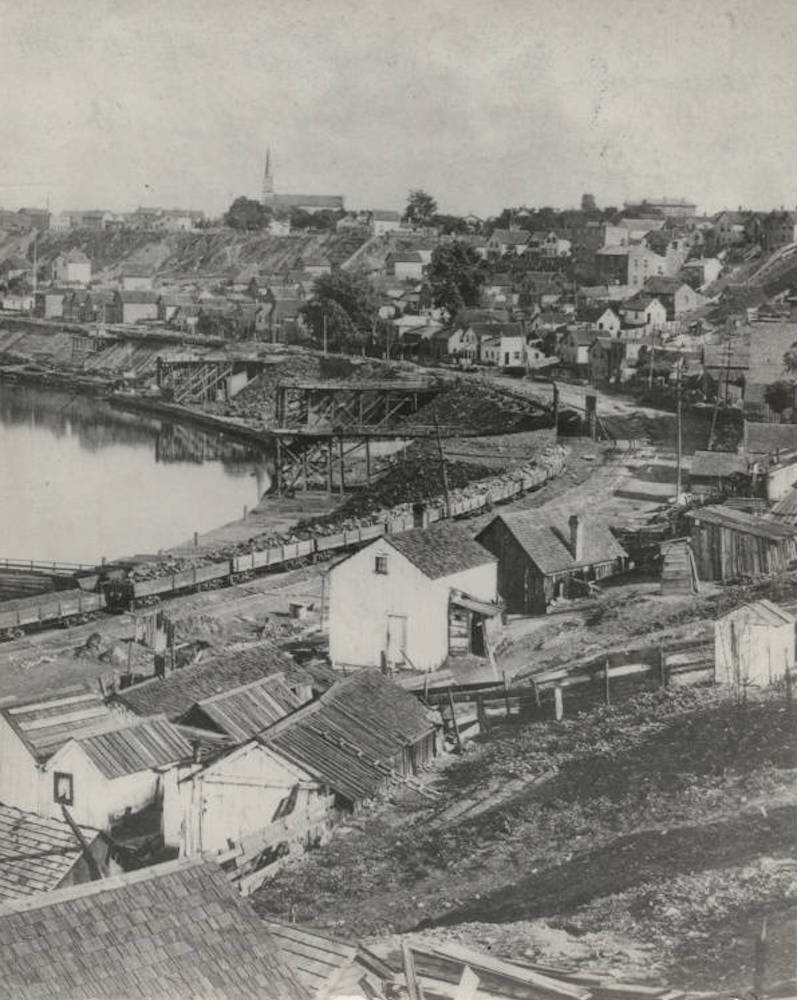

Irishtown Bend

Irishtown Bend Park is a future green space that will honor the city’s 19th-century Irish immigrant legacy. Nestled along the Cuyahoga River, it marks the location where many Irish workers and families once lived while building the Ohio & Erie Canal. The park will serve as a tribute to their role in shaping Cleveland’s landscape.

Irish Bend,” now known as , is named for the Irish immigrants who settled there in the mid-1800s, alongside a prominent curve in the Cuyahoga River. This area on the west bank of the river’s Flats in Cleveland became a dense Irish neighborhood, with many residents working in the shipping industry.

Central Neighborhood

Originally diverse, the Central neighborhood, particularly around East 55th and Central Avenue, became a significant hub for African American families during the Great Migration. Facing segregation and discrimination, Black residents turned this area into a vibrant cultural and political center—home to churches, civil rights activism, and social progress.

Buckeye Road

Known as “Little Hungary,” Buckeye Road was once home to the second largest Hungarian population outside of Budapest. Immigrants created a thriving neighborhood filled with Hungarian churches, bakeries, and community centers. The cultural pride and traditions established here continue to resonate throughout Cleveland.

St. Stanislaus Church

This church was originally built by Polish immigrants in 1866, who sought to establish their own Catholic community and worship space in honor of St. Stanislaus, the bishop, martyr, and patron saint of Poland. As the community expanded rapidly, the parish and its schools grew to serve the Polish population with both elementary and high school programs that included language and cultural instruction. To this day, St. Stanislaus Church remains a cornerstone of the Polish community in Greater Cleveland, hosting events that celebrate both old- and new-world Polish traditions and achievements.

St. Stanislaus is no ordinary church—it holds deep significance in the Catholic world. For example, Pope John Paul II visited the church in 1969, presenting a relic of St. Stanislaus and reinforcing the church’s spiritual connection to the Vatican. In addition, the church is an architectural landmark listed on the National Register of Historic Places, recognized for its striking design and cultural legacy. A visit to St. Stanislaus Church offers a glimpse into Cleveland’s rich Catholic and immigrant history.

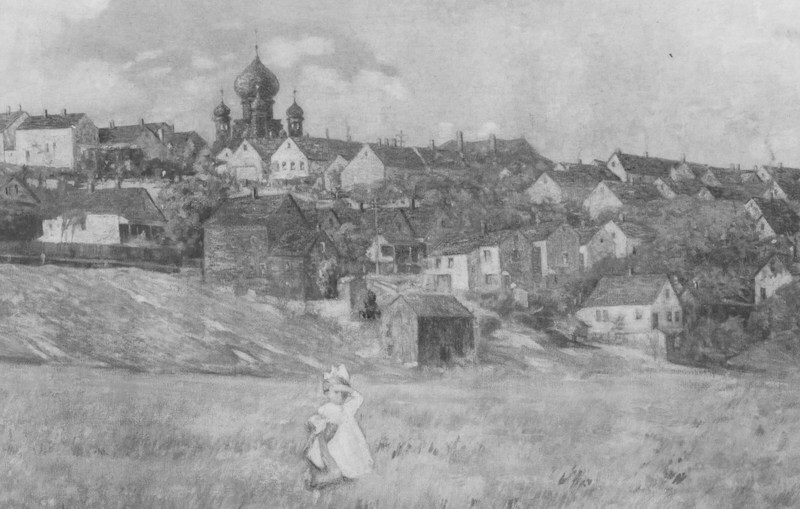

St. Theodosius Orthodox Cathedral

Located in the West Side neighborhood of Tremont in Cleveland, St. Theodosius Orthodox Church is widely considered one of the finest examples of Russian church architecture in the United States and serves as the mother church for all Orthodox parishes in Ohio. In the mid-19th century, Tremont was home to a succession of immigrant communities, many of whom constructed architecturally significant churches. Among them were Rusyn Greek Catholics, who founded the St. Theodosius parish. From its earliest days, the church not only served the Rusyn community but also welcomed Orthodox Christians of various ethnic backgrounds who had not yet established their own congregations.

The current cathedral was completed in 1912, after parishioners had previously worshipped in two other buildings. Father Basil Lisenkovsky provided architect Frederick Baird with photographs of a church in Moscow, which inspired the design of what Baird called “pure Russian architecture.” While the original interior was adorned with paintings imported from Russia, it was later reimagined by Andrej Bicenko, an artist who fled to Yugoslavia after the Russian Revolution. Bicenko introduced a “neo-Byzantine” style, which he described as a more modern interpretation of anatomy and perspective while preserving the traditional Byzantine depiction of garments and figure posture. Today, the history and artistry of St. Theodosius Orthodox Cathedral offer visitors a powerful and immersive spiritual and cultural experience.

Old Stone Church

The Old Stone Church (First Presbyterian Church) in Cleveland, Ohio, developed a significant relationship with the city’s Chinese community, especially during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Standing at the heart of Public Square since 1855, the Old Stone Church is Cleveland’s oldest surviving building on the Square and a lasting symbol of faith, resilience, and welcome. A Presbyterian congregation known for its civic engagement and social justice work, the church has played a quiet but important role in supporting immigrant communities, including Cleveland’s growing Asian population. Over the years, the church has partnered with organizations such as Asian Services in Action (ASIA Inc.) and InterAct Cleveland to host cultural programs, citizenship workshops, and interfaith dialogues that promote inclusion and belonging. Its doors remain open not only for worship but also as a gathering space for community reflection, advocacy, and cross-cultural exchange. As Cleveland’s Asian population continues to grow and diversify, the Old Stone Church stands as a historic institution committed to fostering unity and honoring the contributions of all who call the city home.

Here’s a breakdown of that relationship:

Early Settlement and Support: The Old Stone Church actively worked with Chinese immigrants from their initial arrival in Cleveland. While the Chinese faced significant racism in other communities, the church provided a notable exception.

Missionary Work and Education:

- Starting in 1892, the church operated a Sunday school for Chinese residents, teaching them English and Christian Gospel for 50 years.

- This initiative was seen as a mission, similar to those the church supported in China.

- Two church members, Marian M. and Mary F. Trapp, sisters and public-school teachers, were particularly instrumental in this effort, working with the Chinese community for 30 years and even learning Cantonese to assist with business and other matters.

Community Center and Protection: The church served as a school and community center for the Chinese population. Reverend William Foulkes of the Old Stone Church even defended his Chinese neighbors on the radio against raids and arrests by police, some of whom were not involved in tong feuds.

Continued Support and Legacy: In 1941, the church helped establish the Chinese Christian Center, transferring language classes and worship services there. This established support for Cleveland’s Chinese population helped them become crucial contributors to the local economy and gave them a foundation of support, according to Cleveland Historical.

- In essence, the Old Stone Church became a vital center for education, community building, and advocacy for Chinese immigrants in Cleveland, offering a welcoming environment in contrast to the prejudice they faced elsewhere.

Sources:

Old Stone Church, “History and Mission.” https://www.oldstonechurch.org

Asian Services in Action (ASIA Inc.), “Community Partnerships and Outreach.” https://www.asiaohio.org

Trinity Cathedral

Trinity Cathedral in Cleveland has a long history intertwined with immigrant communities, particularly during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. While not initially founded by immigrants, it became a vital part of the immigrant experience as the city grew and welcomed newcomers from various backgrounds.

Here’s a more detailed look:

- Early Years and Growth:

Founded in 1816 as the first Christian congregation in Cleveland, Trinity initially served the existing community. As Cleveland grew, particularly with the influx of immigrants during the “new immigration” period (1870-1914), Trinity’s role evolved.

- Responding to Community Needs:

Trinity’s outreach extended to various immigrant groups, including Polish, Slovak, and other communities. The Cathedral became involved in providing services and support to these communities.

- A Cathedral for the City:

Trinity’s history is also marked by its role as a cathedral, serving not just its parish but also the wider Diocese of Ohio. This role has involved outreach and social activism, and more recent initiatives focused on racial reconciliation and inclusion.

- Interfaith Solidarity:

In more recent times, Trinity Cathedral has hosted events like the Northeast Ohio Interfaith Solidarity Statement on Refugees and Migrants, demonstrating its commitment to inclusivity and support for immigrant communities according to the Interreligious Task Force on Central America.

Cleveland Guardians Statues

While some Clevelanders may not always recognize the impact of newcomer communities on the city’s identity, their influence runs deep, especially in iconic landmarks like the Guardians of Traffic statues. Though often attributed solely to their designers, few realize that the actual stonework was carried out by Italian stonemasons working for the Ohio Cut Stone Company. Craftsmen such as Bill Anslow, Antonio Chiocchio, and others from Cleveland’s Little Italy neighborhood played a central role in bringing these sculptures to life.

Erected in 1932, the Guardians have long stood as symbols of strength and progress on the Hope Memorial Bridge, which connects Cleveland’s east and west sides. Their significance was amplified in 2021, when the city’s Major League Baseball team was renamed the Cleveland Guardians—a tribute that not only honors the statues themselves, but also the immigrant labor that helped build them.

Today, the Guardians stand as a powerful reminder of the immigrant hands that helped shape Cleveland’s infrastructure, culture, and identity. Next time you’re driving downtown across the Hope Memorial Bridge, take a moment to appreciate the resilience and craftsmanship they represent.

Cleveland Cultural Gardens

Located along Martin Luther King Jr. Drive and East Boulevard, the Cleveland Cultural Gardens are a unique and beautiful collection of public gardens that celebrate the heritage of over 30 different ethnic communities that have shaped Cleveland’s history. Established in 1916, the first garden honored William Shakespeare and the British community. Since then, the gardens have expanded to represent cultures from all over the world, including the Indian, Ukrainian, Chinese, Italian, and Syrian communities, just to name a few. Each garden is designed and maintained by volunteers from that specific cultural group, often incorporating traditional architecture, art, and landscaping styles from their homeland.

What makes the Cleveland Cultural Gardens especially meaningful is their message of peace through mutual understanding. The annual One World Day, held in the gardens, celebrates Cleveland’s diversity with food, music, naturalization ceremonies, and cultural performances. Whether you’re taking a peaceful walk through the winding paths or attending a festival, the Cultural Gardens serve as a vibrant reminder of Cleveland’s immigrant legacy and its ongoing commitment to inclusivity and cultural celebration. It’s a must-visit for anyone seeking to experience the international spirit of the city without ever leaving town.

Richman Brothers Clothing Company

Founded in 1853 by German-Jewish immigrant Henry Richman and his brother-in-law Joseph Lehman, the Richman Brothers Company grew from a small tailor shop into one of America’s most prominent men’s clothing retailers. The company was rooted in the immigrant experience, both in its leadership and its workforce — employing many Eastern European and Jewish immigrants who had settled in Cleveland in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Known for affordable, ready-to-wear suits, Richman Brothers also gained national attention for its progressive labor policies. The company offered profit-sharing, refused to lay off workers during the Great Depression, and promoted racial and religious integration within its factory — an uncommon stance for its time. Its iconic headquarters on East 55th Street, opened in 1917, served as both a factory and a community anchor for generations of Cleveland workers and their families.

Lighthouse Park

In 1893, a delegation from Gdańsk, Poland, visited Cleveland on their way to the World Exposition in Chicago.There, the group saw the 1873 Cleveland Harbor Lighthouse, known as one of the most impressive American lighthouses in history. Later that year, the lighthouse had a Polish twin. Gdańsk’s Nowy Port lighthouse went into operation the following year, and even played a part in World War Two. Gdańsk and Cleveland have had a long history of Migration, cultural exchange, and lighthouses, among other things.

Today, this relationship is honored by Lighthouse Park.

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame has deep connections to immigrants and international influences, both in its stories and in its iconic architecture:

Cultural & Musical Connections

Alan Freed, one of the pivotal figures in rock and roll’s emergence, was the son of a Russian Jewish immigrant father. He played a major role in breaking down racial barriers by bringing Black and white music to broader audiences and was inducted into the Rock Hall in 1986. Many inductees reflect international roots or immigrant identities. For example, Joan Baez’s father was of Mexican descent, and Ritchie Valens—born in California to Mexican parents—brought Chicano rock into the mainstream before his life was tragically cut short. Carlos Santana, who immigrated from Mexico, blended Latin sounds with rock to worldwide acclaim. DJ Kool Herc, often called the father of hip-hop, immigrated from Jamaica and helped lay the foundation for a genre that would influence rock and popular music globally. The Hall has also honored Maná, the first Spanish-language band nominated for induction, highlighting the global and multicultural evolution of the genre.

Architectural Connection

The building itself was designed by an internationally renowned architect:

The Rock Hall’s distinctive structure was designed by I. M. Pei, a Chinese-born architect celebrated for globally influential designs like the Louvre pyramid in Paris. His work on the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame imbued it with a modern, symbolic energy meant to reflect the dynamism of rock music.

The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame embodies global influence both on the inside and out—honoring immigrant stories and cultural diversity in music, and standing as a standout creation by an international architectural master.

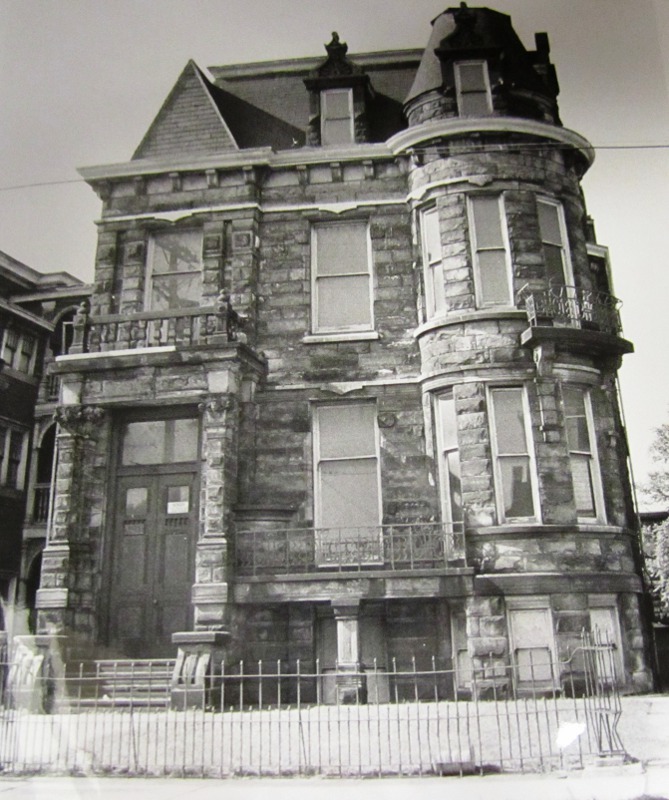

The Franklin Castle (Hannes Tiedemann House)

Built in 1881 and later owned by Swiss American Frederick W. Bomonti, Franklin Castle is a stunning example of Swiss-inspired architecture in Cleveland. The house symbolizes the influence of Swiss immigrants, who brought their culture, design, and craftsmanship to the city in the late 19th century.

Cleveland Public Library

Founded in 1869, the Cleveland Public Library has grown into one of the largest public library systems in the United States, often called “The People’s University.” Its historic Main Library on Superior Avenue and Louis Stokes Wing are notable city landmarks, offering free access to books, technology, art, and educational programming for the community. The Library has a long history of serving residents from all backgrounds, providing resources in multiple languages, citizenship preparation classes, and cultural events that highlight Cleveland’s international character.

In partnership with Global Cleveland, the Library proudly hosts the Sister Cities flag installation. Each flag represents one of Cleveland’s sister cities around the world, honoring friendship, cultural exchange, and a commitment to building global connections. This display welcomes visitors and underscores Cleveland’s historic ties to people and cultures across the globe.

The Urban League of Greater Cleveland

Founded in 1917, the Urban League of Greater Cleveland (ULGC) emerged during the Great Migration to support African American families moving from the South to Cleveland. The organization provided critical assistance with housing, job placement, education access, and urban acclimation, all while confronting the systemic racism and discrimination that limited opportunity. From the beginning, ULGC promoted economic self-sufficiency and community empowerment, serving as a vital lifeline for families seeking a better life in Cleveland.

Over the decades, the ULGC’s mission has evolved to meet the changing needs of the Black community—expanding into areas like school desegregation, workforce development, and civic engagement. Today, it continues to champion economic empowerment, youth programs, and equity initiatives throughout the region. A visit to Cleveland isn’t complete without acknowledging the work of the Urban League, an institution that has helped shape the city’s path toward greater justice and opportunity for all.

CentroVilla25

CentroVilla25 (CV25), which soft‑opened at the end of 2024 and held its official grand opening festival in May 2025, is Cleveland’s new Latino community hub located at 3140 West 25th Street in the La Villa Hispana district. Inspired by Old San Juan architecture, the 32,000‑square‑foot adaptive‑reuse site houses a Latin food hall with eight food kiosks, micro‑retail stalls, a rentable commercial kitchen, an outdoor plaza, and offices for the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce and Hispanic Business Center.

Founded by the Northeast Ohio Hispanic Center for Economic Development (NEOHCED), CentroVilla25 supports Hispanic and Latino entrepreneurs by offering technical training, affordable retail space, and a supportive business incubator. It aims to uplift the local Latino community, create approximately 190 jobs, and anchor a vibrant commercial corridor along West 25th. As part of Cleveland’s Spanish‑speaking immigrant legacy, CV25 celebrates cuisine and culture from Venezuela, Mexico, El Salvador, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and more; it is quickly becoming a must‑visit destination for community gathering, economic opportunity, and cultural enrichment.

Slovenian National Home

Located in Cleveland’s St. Clair–Superior neighborhood, the Slovenian National Home was built in 1924 around the former Diemer Mansion and remains the largest and most significant Slovenian cultural center in the United States. Originally envisioned as a “national home” for Slovene immigrants, it offered a gym, library, auditorium seating over 1,000, and meeting rooms for dozens of fraternal, social, and cultural societies. In partnership with St. Vitus Catholic Church, it served as the spiritual, civic, and cultural anchor for generations of Slovenes in Cleveland and its surrounding suburbs. Throughout the 20th century, the Home hosted operas, debutante balls, polka festivals, dramatic societies, and singing groups like Zarja and Jadran. Today it continues as a vibrant community venue, home to the Slovenian Museum & Archives, and hosts signature events like Cleveland Kurentovanje—a Slovenian‑style “Mardi Gras” celebrated every spring. The Home remains a living testament to the Slovene immigrant legacy in Greater Cleveland, bridging history, heritage, and neighborhood unity.

Ukrainian Museum Archives

Founded in 1952 in Cleveland’s Tremont neighborhood, the Ukrainian Museum-Archives (UMA) was established by displaced scholars who sought to preserve Ukraine’s cultural legacy at a time when such materials were being actively destroyed in Soviet Ukraine. From the very beginning, the mission of UMA was to safeguard books, newspapers, folk art, and historical documents that might otherwise have been lost forever. Over its first 25 years, the museum amassed an extraordinary collection, including many rare and unique items, making it one of the most significant repositories of Ukrainian history and culture outside Ukraine.

Today, UMA continues to serve as a research center, museum, and community space. It hosts exhibits, lectures, and educational programs that highlight the Ukrainian American experience while also connecting Cleveland’s community to global Ukrainian history. In times of crisis, such as Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine, UMA has provided cultural grounding and a sense of continuity for Ukrainian Americans and others interested in the preservation of heritage.

Sources:

Ukrainian Museum-Archives: https://www.umacleveland.org